Poundbury, a mixed-use urban village that is an extension of Dorchester, a country market town in southwest England, has achieved notoriety – internationally as well as within Britain—that was assured if only because of its famous patron, the Prince of Wales. The 400-acre (162 ha) site is intended to accommodate a series of mixed-use neighborhoods, of which 20 percent of the housing will be affordable, as well as 150 acres (61 ha) of open space, and retail and private workplaces—all mixed into a compact arrangement.

Poundbury, a mixed-use urban village that is an extension of Dorchester, a country market town in southwest England, has achieved notoriety – internationally as well as within Britain—that was assured if only because of its famous patron, the Prince of Wales. The 400-acre (162 ha) site is intended to accommodate a series of mixed-use neighborhoods, of which 20 percent of the housing will be affordable, as well as 150 acres (61 ha) of open space, and retail and private workplaces—all mixed into a compact arrangement.

As explained in Price Charles Foundation’s small book, Civitas, Poundbury exists as a working lesson for England’s planners, architects, critics, and most important, consumers. At the least, it is intended as an antidote to the 20th-century adoption of the international style of architecture (also akin to modernism), whose ultimate and best-known example in the United States was the Pruitt Igo high-rise public housing in St. Louis, and comparable examples in hundreds of other American communities.

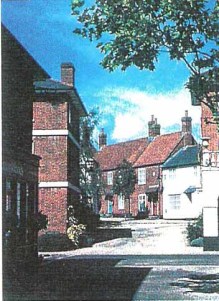

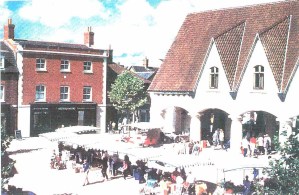

Where modernist architect Le Corbusier conceived of tower blocks soaring upward from high-speed roadways, Poundbury offers two- and three-story structures for living, working, shopping, or a pub lunch. Where Corbusier’s Radiant City model of apartment buildings (Les Unites) isolated humans in elevator towers, Poundbury manages to bring them together in intimate settings and walkways. Where the international style produced single uses in buildings that discouraged human intercourse, Poundbury emphasizes the social side of life and spontaneous encounters, relishing the pedestrian dynamic. Where Corbusier saw long, straight predictable lines, Poundbury presents a mazelike, irregular mix of streets and lanes, a bit reminiscent of ancient Rome. Where Corbusier placed people and buildings out of the way so that cars could proceed at full speed, Poundbury’s plan moves cars out of the way so that pedestrians can move unimpeded.

Poundbury is a tangible, marketable, working expression of Prince Charles’s philosophy of planning, designing, and building expressed in his book written 15 years ago, A Vision of Britain. Earlier, Prince Charles had offended much of the ruling caste of British architects with his criticisms of the places then being constructed. Something of a populist in design matters, he wrote “… I get a very strong impression that most people know the sort of buildings they like …[Ones] that have grown out of our architectural tradition and that are in harmony with nature.” Speaking of “principles that we can build on,” he wrote:

Poundbury is a tangible, marketable, working expression of Prince Charles’s philosophy of planning, designing, and building expressed in his book written 15 years ago, A Vision of Britain. Earlier, Prince Charles had offended much of the ruling caste of British architects with his criticisms of the places then being constructed. Something of a populist in design matters, he wrote “… I get a very strong impression that most people know the sort of buildings they like …[Ones] that have grown out of our architectural tradition and that are in harmony with nature.” Speaking of “principles that we can build on,” he wrote:

“The principles aren’t commandments at all, but more like pieces of folklore drawn from our inherent experience; rules that we have put into practice for centuries without thinking too much about it and which resulted in Britain having some of the most beautiful towns and cities in the world.”

“The principles aren’t commandments at all, but more like pieces of folklore drawn from our inherent experience; rules that we have put into practice for centuries without thinking too much about it and which resulted in Britain having some of the most beautiful towns and cities in the world.”

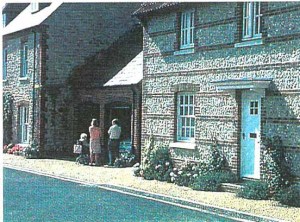

The principles, together with the Poundbury building code, have shaped a most likable settlement. The design and construction of every building is required to comply with the building code. The design guidelines for residences cover extensions of original buildings; building materials and details; walling materials; lintels; outbuildings; roofs; roof lights (skylights); rainwater hardware, gutter, and plumbing; chimneys; windows (aluminum frames are not permitted), doors, and porches (metal doors are not allowed); subsidiary elements (bubble skylights are forbidden); and walls, fences, and gardens. Despite the prohibitions, the overall presentation of Poundbury’s building  code is positive, with drawings and photos to illustrate permitted applications.

code is positive, with drawings and photos to illustrate permitted applications.

Because these rules and suggestions have been applied by a variety of architects (more than 30), Poundbury manages to reflect both harmony and diversity, an unusual and pleasing combination. The guide is candidly retrospective in its orientation: “Poundbury is a living demonstration of the application of refinements in place making.” Poundbury is not intended to be a “new town” like British and American new towns. Rather than alter or improve on past development, or invent a community form for the future, it seeks to refine historic community evolution.

English new towns –such as Washington, Northampton, and Peterborough—and other U.S. new communities –such as Columbia, Maryland; Reston, Virginia; and Radbury, New Jersey—present a different emphasis in applying planning rules. In new towns, a conscious effort is made to create a new model of community, less radical and significantly more human in scale and orientation than the International style, but akin to it in the assumption that the 20th-century required a town that was different from the communities that emerged in the 19th century. The designers of Poundbury strove to use and exploit the best from the past. Poundbury achieves this without the mock Tudor and other derivative house styles that imitate the English as well as the American past in many older U.S. towns. Without being “modern,” it also is not faux anything.

Poundbury provides the English with more of what they already have: cleaner and tidier inside and outside edges, and better kitchens and baths than were available in the traditional English village, of which a great many remain. Yet, there are many similarities to the compact semi-urban village environment that have existed for generations. With its own village-centered pub, for example, Poundbury offers a place to chat with those who live nearby, while jobs and shops are within walkable distance for many residents.

Planners of Poundbury were determined to break away from conventional, land-hungry, car-dominated residential developments that have eroded the setting of many historic towns and villages. “Highway engineering standards, garages, and parking provisions have often determined layouts. leaving little room for buildings to be grouped with any real sense of identity,” explains the introduction to the Poundbury design standards booklet.

Forty percent of Poundbury’s households are retired, which is in line with the percentages of retired households in England ‘s southwest counties, and the level of affordable dwellings has increased from 20 to 35 percent, reports Simon Conibear, Poundbury’s development manager. Expansions are adding more dwellings to the completed Phase I plan, attracting buyers from as far away as Canada.

How was Poundbury influenced development in Britain? British urban designer Alan Baxter says it has had a “catalytic effect,” but adds, “We have a long way to go before we get completely away from the banal housing estates of culs-de-sac and detached homes that still dominate in the U.K.” Baxter observes that Llandarch, South Wales, and Upton in Northampton, England, advance the Poundbury ideas even further. However, he is concerned that content will be corrupted should builders adopt a part of Poundbury’s most obvious virtues without the essential “depth of thought” required to make the principles work in other settings. Poundbury’s real success, he says, comes from “its challenge to rule-based traffic engineers who have required too much vehicle maneuvering space at the expense of human-scale lanes.”

Back through history, two contrasting systems of streets have shaped urban places. The Romans, who settles throughout Europe, created the grid system, which later shaped such cities as Savannah, Georgia, and much of Manhattan, both planned places. Earlier, in London, for example, street patterns were highly irregular, producing unpredictable scenery. Poundbury is clearly of the irregular school; street and footpaths occur where buildings do not. Far more interesting to the eye, such an arrangement probably encourages more walking, simply because it is more interesting to walk in such a variable setting. In large, dense urban areas, such as Center City Philadelphia, automobiles become more of a nuisance than a convenience. The only way they can move is very carefully; there is no need for corrective traffic-calming measures.

Back through history, two contrasting systems of streets have shaped urban places. The Romans, who settles throughout Europe, created the grid system, which later shaped such cities as Savannah, Georgia, and much of Manhattan, both planned places. Earlier, in London, for example, street patterns were highly irregular, producing unpredictable scenery. Poundbury is clearly of the irregular school; street and footpaths occur where buildings do not. Far more interesting to the eye, such an arrangement probably encourages more walking, simply because it is more interesting to walk in such a variable setting. In large, dense urban areas, such as Center City Philadelphia, automobiles become more of a nuisance than a convenience. The only way they can move is very carefully; there is no need for corrective traffic-calming measures.

Are Poundbury’s principles and rules overly rigorous? Do they produce an environment that is all of a single piece—cookie cutter homes hard upon one another? Actually, Poundbury comes across as a place of unusually distinctive residences, less monochromatic, for example, than the beige stone villages in the English Cotswolds.

Poundbury is modest in at least one respect. The plan for the distribution of retail, homes, and workplaces assumes a five-minute walk from place to place. Office workers in U.S. downtowns average nine minutes in walking from desk to destination, exposing them to almost double the number of shops and restaurants that can be reached in a five-minute walk. The English are known for the pleasure they take in walking, suggesting that as Poundbury expands and adds destinations, the average walking trips also will lengthen.

Asked if there have been any different in applying the principles and guidelines, Poundbury representative Edward Taylor says that the “stipulations” that each resident signs when they move in have had the desired result: in effect, they have introduced “self policing.” Each household believes that everyone’s adherence to the stipulations benefits everyone’s property values. When Poundbury’s rules were new, they were ahead of the design standards then in effect in most British communities. National standards have since begun to catch up, according to Taylor, and Poundbury’s guidelines have been expanded to take into account new energy and environmental rules.

Taylor explains that developers respect the Poundbury system in part because it helps them anticipate constructions costs. He is conservative in estimating the impact Poundbury has had on development practices elsewhere, but notes that 100 local authorities, NGOs (non-governmental organizations), and developers typically travel to Poundbury annually on official visits, and that an estimated 30,000 “unguided” visitors come out of curiosity from what they have heard about it.

Would Poundbury work in the United States? The experience of the new urbanist developments and of golf courses and retirement planned communities, each with detailed design requirements, suggests that something like the Poundbury model might well succeed. Some American householders are showing a preference for locations where they will be protected from adverse changes. Homeowners associations and historic commissions armed with design guidelines tend to apply the guidelines rigorously to preserve over the years the original appearance and condition of the place they have long called home.