Manhattan’s Times Square just received its first “A” on the Mayor’s Sanitation Scorecard. In that once glittering entertainment district where more recent visitors complained of filth and criminals, sidewalks are again clean, crime has dropped off, and tourists are reassured.

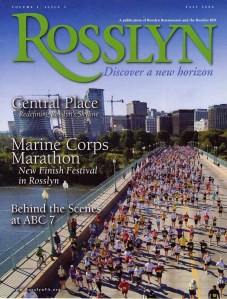

In Philadelphia, 2,000 surveyed property owners, employers, workers, residents, and visitors said conditions in the Center City area had improved markedly for the second consecutive year. The area received high marks for safety, cleanliness, and general atmosphere. After dark, sidewalks are crowded – with shoppers, diners, and entertainment seekers. Free concerts by famous mummer bands, jazz ensembles, and classical groups are popular.

After decades of bad press, this kind of downtown success story is becoming widespread. At its heart is a quiet revolution concerning who takes responsibility for the “operations” of downtown commercial areas. Rather than blaming City Hall or working for a blockbuster federal subsidy, hotel operators, theater owners, storekeepers, restaurateurs, service providers, office employers, developers, property owners, and property managers are planning and managing urban services in their neighborhoods. Believing that these services an! essential to a commercial precinct’s economic vitality, these stakeholders are paying for them as a cost of business. The payments arc like the common area maintenance charges paid by shopping center tenants. In New York City, self-imposed charges for urban services for 24 improvement districts amount to more than $30 million annually. Furthermore, business leaders are devoting considerable time as well to these improvement efforts.

This article examines business improvement district (BID) trends in large downtowns, drawing on surveys of 13 illustrative assessment-financed districts. These are called special assessment districts, special services districts, business improvement areas (BIAs), or business improvement districts–depending on the state laws that authorize them. Whatever their names, BIDs have several key elements in common:

- The initiative comes from business leaders who seek common services beyond those that the city can provide.

- The city determines boundaries, approves the annual budget and the financing strategy, and determines what services may be provided.

- Business leaders shape the annual budget, hire staff, let contracts, and generally oversee operations.

New York City BIDs

A 1993 study by the New York City Partnership and The Atlantic Group of the city’s 24 BIDs (about 30 more are in the process of being formed) found annual budgets that range from $82,000 to more than $9 million for the Grand Central Partnership. At 17 years old, Brooklyn’s Fulton Mall is among the nation’s oldest BIDs. One of d,ese BIDs deals exclusively with the maintenance and improvement of Bryant Park, and rents in nearby buildings have soared since d,e park was redesigned and secured.

Eight of the N ew York City BIDs have budgets of more than $750,000, with the average being $3.6 million. As shown in Figure 1 on the preceding page, they spend most of their funds on cleanup, sanitation, and litter patrols, followed by supplemental security and capital projects. About 11 percent of their budgets are allocated for administration. These large BIDs see their greatest need for action as filling commercial vacancies, followed by improvements in buildings, public areas, and the overall image of the district.

Five large Downtown Improvement Districts

A 1994 survey of BIDs in Denver, Houston, New Orleans, Philadelphia, and Seattle provides further insight on the politics, progress, problems, and typical approaches of large BIDs. Like those of New York, d,ese BIDs also spend at least half their budgets on cleanup and security. (Small BIDs, on the other hand, tend to give greater emphasis to marketing, special events, parking, and business attraction.)

Denver. The Downtown Denver Business Improvement District began life in 1982 as the 16th Street Mall Management District. The core of the 120-block district is the 16th Street transit and pedestrian corridor. Each day, its free shuttle buses move 45,000 downtown employees, 42 percent of the workforce. Its foundation was supported by virtually everyone, from city government officials to building owners and managers, from retail and hotel associations even to residents o f downtown.

BID president Bill Mosher and a 12-member board, composed of property owners, bankers, a realtor, and other area business people, work with a $1.9 million budget. This buys sidewalk litter pickup and snow removal; landscaping and maintenance of trees and flowers; lighting, electrical, and plumbing services in public places; granite paver maintenance; snow removal; banners; regulation of commercial and other use of public space, including sidewalk vending; business retention and attraction efforts; marketing , communications, and promotions; and supplementary security services. A four-member staff handles publicity, special events, business recruitment, and the like and contracts out for security, snow removal, landscaping, and other services.

Costs are shared by 323 property owners under an unusual assessment formula by which fees decrease with distance from the transit-pedestrian mall. Data on crime rates, cleanliness, and retail sales, as well as business own er surveys, have shown strong improvements over the past several years and a high degree of satisfaction. The least satisfied people are property owners farthest from the mall. Participants believe that what most needs improvement is the appearance of buildings and commercial areas. Seattle. Founded in 1986, the Downtown Seattle Association (DSA), with a $577,500 budget, provides a variety of services including public relations, marketing, security, sanitation, and retail promotions.

Assessments are collected by the city. As in Denver, the assessment formula has different rates reflecting different levels of benefits. (Many states have laws that allow BIDs only one or very few choices in assessment rates.) DSA applies a different rate to five classes of properties in its retail core-developed ground-floor business space, retail space in basements or in second or third floors; major multilevel retail stores with more than 100,000 square feet under single ownership; parking garages and lots; and other properties, including hotels and theaters. Parking facilities, for example, arc assessed $4 per space for marketing purposes and $2 per space for maintenance. In addition, DSA’s marketing program and common area maintenance programs have their own separate assessments reflecting different degrees of benefits for different types of properties. The Seattle district is headed by John Gilmore, a seasoned downtown executive.

New Orleans. The oldest of the big city BIDs — established in 1975 –the New Orleans Downtown Development District is key to what makes the Crescent City attractive to millions of visitors. With an annual budget of$3.6 million, Donald A. Shea and a small staff provide a wide range of services for 3,000 businesses in 200 blocks. In addition, a capital improvement program supports new street trees, lighting, trash containers, and banners. Shea reports that the most difficult part of forming the BID was reaching an agreement on the district boundaries. The New Orleans Chamber of Commerce, the city government, and the retail organization combined to produce the agreed-upon program.

Philadelphia. One of the newest BIDs is Philadelphia’s Center City District. Formation of the district was an important part of the plan for the city’s commercial core that was adopted in 1991. Developer Ron Rubin chaired the group that set service priorities (sidewalk cleaning and supplementary security), delineated the service area (80 blocks), and recommended the budget (now $6.5 million). Reflecting the value of the area’s newest skyscrapers, 15 properties pay approximately one-third of the total assessment. The amount paid by most of the district’s 9,000 businesses is very small.

Center City is a popular place in which to live as well as work, and distinctions between residential and commercial areas are blurred. When the proposals for forming an improvement district were broached, many residents objected to paying for the supplementary cleaning and.security. Their opposition might have jeopardized adoption of the assessment district by the city council. Because state law would not allow noncommercial property owners within the district to be exempted, a rebate system was created to satisfy d,e opposing residents.

Rubin now chairs the 23-member board that oversees a staff of 54 uniformed security-hospitality employees and 11 5 sidewalk cleaning employees under contract. Under the direction of executive director Paul Levy, COD recently completed a streetscape plan for 80 blocks of Center City geared to pedestrian visitors, downtown employees, and shoppers. Convention Center attendees, for example, will find signs directing d,em to their hotels, to theaters, to shopping areas, and to historic sites, with information on how many minutes the walks will take. Funding for its implementation is expected to come from an assessment-based capital improvement program.

Houston. Robert Eury, president of the Houston Downtown Management Corporation, works with a 42-member board of which 12 are nonvoting local officials. Houston’s BID has a $2.6 million annual budget, 88 percent of which is derived from an assessment of $0.06 per $ [00 of assessed valuation of land and improvements. Major support for organizing the district, which comprises 212 blocks and 360 property owners, came from the chamber of commerce, the local Building Owners and Managers Association, and the city government. Established in 1991, d,e district emphasizes removal of crime and grime, streetscape and commercial theater improvements, and special events. The district measures success by comparing conditions with its adopted multiyear plan, by opinion surveys, and by regular reporting on litter conditions using comparative photos.

Who Participates? Who Pays? How Much?

Time and money are two fairly reliable measures of business support for any community enterprise. Figure 2 on page 14 shows the range of board of directors membership for the surveyed BIDs. Landlords, property owners, and real estate interests constitute the largest single group of board participants. (In smaller BIDs, retailers tend to dominate the governing boards.) The boards of large BIDs include varied business interests, as well as a small number of elected and other local officials, sometimes without voting privileges. The average size of New York City large BID boards is 30 members and of other city boards is 35 members. Many other men and women sit on BID working committees. New York City BIDs have working committees on security that average ten members, marketing (nine members), retail promotions (11 members), and business recruitment (nine members).

In most cases, state law requires some form of vote by those affected, either before or after the city council passes an enabling ordinance. It may take months or occasionally years before consensus is reached in debates about whether to create a district; what its boundaries, goals, accountability, and representation in decision-making should be; and how costs should be shared. However, as a business world intramural -discussion, these debates are not a contest between the public and private sectors. City councils are inclined to accept d,e business-defined plan, if only because resident taxpayers are rarely called on to share the charges.

BID charges typically are included in the pass-through provisions of commercial leases. Philadelphia’s Center City District collects about $0.13 per square foot per year, a fairly typical charge, although the assessment formula commonly is expressed in terms of a property’s assessed value. Large property owners bear a major share of the costs. But they tend to support BIDs because such organizations offer the only conceivable way to assure the maintenance of the neighborhood beyond their own properties.

To afford latitude to businesses and minimize the fear or reality of political interference, the management entity generally is a quasi-governmental body or a designated nonprofit corporation. In most cases, improvement districts are formed by existing downtown organizations. The downtown organization may take the concept only to the planning/negotiation stage or it may actually combine its own and the improvement district’s board of directors and operate both with a single executive.

The growth of BIDs-there are about 1,000 in the United States and Canada-has swelled the ranks of professional downtown executives. The best are sometimes the objects of bidding wars between downtown districts. The meetings of the International Downtown Association, a Washington, D.C.-based professional group, serve as a marketplace for ideas and jobs.

Fighting Fear

Although CBDs generally are among the safest areas of large cities, these BIDs invest heavily in security and related programs in order to deal with the public’s fear of crime in cities. They have used several approaches.

More Police. Some large city BID budgets pay for additional uniformed, armed policemen. Most such programs emphasize walking patrols.

New Techniques. Many BIDs measure and report on the city’s performance in providing security. Some have sought improved police functioning by purchasing equipment, like drug surveillance cameras or bikes, that the city cannot afford. Philadelphia’s Center City District, policed by two separate precincts, neither of which had the resources to concentrate on the special needs of a major commercial area, provided a facility that police share with CCD’s unarmed, uniformed community service representatives (CSRs). Police welcomed the upscale quarters and have come to see the CSRs as allies, not as “rent-a-cops,” as they have often been portrayed elsewhere.

Unarmed, Uniformed Personnel. Efforts to provide a reassuring security presence do not always justify the costs. In Philadelphia, however, incident reports show that a force of identifiable personnel with radio access to police or other emergency services can be enormously helpful and create good will. The help that these personnel provide people who become lost or sick or who run out of gas, for example, earns the CSRs (and the downtown) much gratitude, special commendations, and good public relations.

Indirect Measures. People base their fears of downtown more on appearances than on actual experience. Litter, ugly security gates across storefronts, graffiti, neglected commercial facades, and vacant stores and buildings imply that the area is out of control. Anticrime initiatives by BIDs include investing in measures to correct such conditions. Streetscapes are redesigned and relighted. Promotions and entertainment are scheduled after work hours to induce word-of-mouth advertising about downtown’s after-dark security.

Street People. Commercial areas attract panhandlers. Some BIDs use their security personnel to discourage aggressive panhandling. Others encourage contributions to shelter and alcohol and drug treatment programs while they discourage people from handing out money or food on the sidewalks. New York’s Grand Central Partnership provides and improves shelter for homeless persons.

State Rules

Behind every BID is a state law. A few states, including Ohio, still lack authorizing legislation. Various states enforce various restrictive conditions. New Jersey authorizes services, but not capita l programs. New Hampshire closely restricts assessment formulas. Few states allow nonprofit corporations to administer districts. Indiana requires unreasonable tests to prove the support of property owners. Connecticut restricts the size of eligible municipalities. Pennsylvania does not allow localities the option of confining the assessment to commercial properties.

Despite its limitation on borrowing, the New Jersey law contains many strong features that ease the process of setting lip BIDs and that minimize the potential for political interference in the operations of BIDs. In New Jersey, business leaders can organize a district without much trouble. They sometimes poll property owners. but a vote is not a requirement. The business community can dominate the board of directors, freely determine the size and composition of the board. and use a nonprofit corporation to run the BID. Any system of assessment that reasonably relates to the benefits received is allowable. Non-benefiting properties, such as residential or industrial properties, may be excluded from the assessment, and tax-exempt properties may be included. Although the city council must approve the annual budget, BIDs need not be staffed by government employees, apply local bidding rules, nor subject their board members to state disclosure rules or restrictions on working with government agencies. Finally, the New Jersey law authorizes BIDs to offer a wide array of services and improvements.

State laws make a difference. Pennsylvania, with its restrictions, has fewer than a half-dozen districts. Less populous New Jersey has more than 20. Few New Jersey BIDs took more than nine months to meet the legal tests and to convince business people and elected officials to support them. The five large city BIDs surveyed averaged 16 months preparing for and securing approval of their ordinances. The New York City BIDs averaged 32 months.

Do They Work?

A number of problems or potential problems deserve mention. For example, the control of city councils over annual budgets makes political interference a constant possibility, though little has yet been reported. As more BID budgets top $1 million or $5 million, it would not be surprising if politicians sought to use BIDs to cut deals, fill jobs, or influence contracts outside the spotlight of public scrutiny.

Oversight of operations could be a problem for some BIDs. Most boards pick their members from a relatively small pool of volunteers. But even where city councils approve board members, meaningful accountability, checks and balances, and public scrutiny usually are absent. New Jersey requires that one board member also be an elected member of the city council, which improves communication and may have averted some mistakes. It is wise to include a five-year sunset provision in the legislation creating individual BIDs, which would offer cities and districts the opportunity to reconsider initial assumptions in light of actual performance.

BIDs often adopt programs that have worked for other BIDs. They would do better to invest more time in understanding conditions and in identifying the preferences of the rank-and-file business operators in their own districts.

Some observers fear that if downtown businesses no longer need to lobby for special services through the city-wide budget process, there will not be enough taxpayer pressure on cities to spend for police or other essential services. Others observe that spending for downtowners does not benefit residents in general, and the poor in particular.

These complaints miss the point that the cleaning needs for downtowns are many times greater than for residential areas, because of high volumes of foot traffic and the downtown’s need to compete with office parks and shopping centers where standards are high. Furthermore, a successful downtown produces economic benefits throughout the city. For example, Philadelphia’s Center City area, occupying only 2 percent of the city’s land, produces about one-third of the jobs and local revenues.

Do BIDs work? Large and small businesses vote with their checkbooks annually to continue and sometimes expand assessment-financed special services. The International Downtown Association knows of no city of any size in which a district has been discontinued. Business leaders have used them to make downtowns, if not perfect, at least demonstrably better. That, perhaps, is the key to their success. Business judgment is being applied to make business districts more profitable.

Many older commercial centers posed challenges for small BIDs because shops weren't open when working people wanted to shop.