For 30 years, Americans have been told that manufacturing is less and less important to the nation’s economy, that the jobs have flown away and the businesses have died. There is more than an element of truth in these generalizations. While manufacturing’s share of gross domestic product shrank from 21.7 percent to 18.4 percent in the 1980-1990 decade, the work force declined from 21.9 million to 21.1 million in the same period.

In the nation’s cities, the losses have been proportionately greater. Indeed, the decline of manufacturing is probably the single largest factor that explains the loss of jobs, businesses, residenls, wage levels and fiscal stability of cities.

Having acknowledged the losses, it is nevertheless important to pay greater attention to what remains of this sector. In Philadelphia, for instance, there are still 90,000 manufacturing workers. Such firms are especially important because these plants tend to be close to working class neighborhoods whose workforces are still a good fit for production jobs.

The preponderant pessimism about manufacturing and cities may help explain why the businesses that remain have received so little attention, even in the cities where they are most important. Little of value is published on why some firms remain or on the specifics of why others leave, although there is no shortage of opinions on the latter. Further, the at risk firms appear to have needs unrelated to the loans, grants and tax incentives designed to attract businesses from outside the jurisdiction or to spur plant expansions among those still within.

By examining five clusters of such firms, all in gritty urban industrial settings in the East and Middle West, some insights resulted suggesting that:

• These city locations continue to provide important benefits for many firms.

• Although the businesses tend to see their problems as place-related, they also see these as surmountable difficulties.

• An encouraging number evidence a willingness to contribute time and money to work together to overcome the deficiencies of their urban environments.

There is also anecdotal evidence that failure to deal with accumulated place·related problems such as crime, trash and governmental neglect incites the frustration that induces some La move away. Despite this, governments rarely see the connection between economic development goals and the provision of the minimum elements of civi lity required by any firm worth retaining.

These five cases have the common feature of having prnduced co llaborative effo rts by groups of business owners and mangers to improve their areas and to secure together improvements that no one of them can accomplish alone. For this feature, they have been termed Industrial Cooperation Areas (ICAs). The five ICAs are:

- PRIDE, (Port Richmond Industrial Development Enterprise), Philadelphia, PA

- Richmond Corridor Association, Philadelphia, PA

- Camptown Industrial Park, Irvington, NJ

- ICLL Industrial Park Association, Detroit, MI

- Bunker Hill Special Improvement District, Paterson, NJ

ICAs: Where They Are, What They Do

The five Industrial Cooperation Areas provide a picture of comparable se ttings and diverse responses. The common elements of these environments can be summarized as follows:

- A concentration of small and medium size manufacturing and distribution firms in areas originally defined by a rail spur.

- The areas are old enough to be adjacent to working class neighborhoods and most still have a good percentage of walk-to-work employees.

- Trucking is essential, although the street layouts dating from horse and wagon times often make maneuvering difficult. Access 1.0 an interstate highway is essential.

- While some still have multi-story manufacturing buildings (notably Philadelphia), most operate in one-story structures. Land acquired for nineteenth century uses is oft.en cramped for today’s spreading buildings, truck areas and employee parking.

- Despite all the problems, many viable 6nns remain and prosper.

In the main, these areas rece ive lillie attention from economic development agencies. Financial incentives designed to lure firms have little relevance to inducing firms La slay. Indeed. a common complaint among industrial plant owners is the disparity between the sometimes staggering subsidies paid to attract new firms and the lack of attention given to those who have long paid city taxes, but are demonstrably neglected on such fundamentals as police protection, street repair and trash removal.

To what extent do the business operators in these aIcas have common problems and priorities for improvement? In three of the areas, similar surveys were used at the onset of planning to identify what the owners felt were the issues most important to pursue. Two areas in Philadelphia, only blocks apart, and a third in New Jersey have expressed both common and disparate needs. Asked whal conditions were “getting worse,” for example, the two nearby Philadelphia areas ranked their responses differently (Table l)

Asked what improvements are needed “a lot,” one Philadelphia area had security as its lop Deed, while the neighboring district did not list it in its top four needs (Table 2). No need turned up in the top four of all three areas.

Taken together, eight area needs in Table 2 reflect common views of urban industrial America, even though the rankings differ. Of interest is the strong concern for improving the appearance of these gritty urban places. 00 one level, this is expressed in a willingness to share cost of regular cleaning and to maintain the constant fight against graffiti. Beyond these, howeve r, districts are also supporting master plans that include such intended improvements as these in the PRIDE report:

- Plant new trees.

- Improve building appearance and signage.

- Clean and paint railroad bridges.

- Create gateway signs.

Case Studies

Case 1: Port Richmond Industrial Development Enterprise (PRIDE). Philadelphia, PA

Port Richmond Industrial Development Enterprise, Inc. (PRIDE) was formed by Alan Woodruff, CEO of Haskell-Dawes, and other owners in 1998 with assislaoce from the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corp. and the Pew Charitable Trusts. With 55 businesses in a eight-block area, the district borders a hospital, residential blocks and an elevated rail line. The economic life line of the area is rnterstate 95 whose access points are co nfusing and. despite a new ramp, still limited for large trucks connecting plants to suppliers and customers from as far away as Georgia. This is the oldest of the five areas with some remaining multi-story brick facilities and everywhere nineteenth century streets and sidewalks that delay truck use (docking one can take a half hour).

To shape their priorities, sleering group members interviewed all the business owners, with some of the survey results discussed earlier. The PRIDE businesses see crime as a major issue and are operating a contract security program. Businesses contribute to lhis and to the contract cleaning service, although City runds sti ll cover most of the cosls. PRIDE subsequently engaged a consulting team to produce an industrial master plan primarily lo deal with physical problems, make improvements to the area’s appearance and create some of the advantages seen in suburban industrial parks. The plan identifies:

- Priority actions to overcome physical and operational constraints to business retention and growth;

- Opportunities to exploit highway access and the skilled labor force;

- Improvements needed for greater truck mobility;

- Land reuse strategies for manufacturing, parking or greenspace;

- Physical improvements to improve streets, sidewalks and public space; and

- Improvements to increase security.

Following are the four elements of the PRIDE plan:

1. Identity and Orientation: A New Philadelphia Address

A key component of the district’s improved image will be a unified sign system that will mark the connections between the PRIDE industrial park and the regional highway network so that visitors can efficiently locale the districl and its businesses.

The steps:

- Develop standards for business and building identification.

- Design and install wayfinding signage system (trailblazer directional markers, 1-95 directional signs, arrival signs, district street identification, parking lot identification, and loading zone identification).

- Develop district signature banners.

- Develop district graphic treatment and illumination for rail bridges.

- Identify and remoye obsolete signage through the district.

- Deyelop profile of desirable PRIDE business types. Develop Overlay Zone ordinance language to support desired uses.

2. Expediting Business: Loading Trucks, Parking Cars

Truck loading must olkn happen in the streel. This blocks busy streets and requires more work than does a well-designed, truck-accessible, loading dock. A preferred truck access route will minimize contact with residential neighborhoods. Over half of the PRIDE businesses report a serious current parking problem that will worsen with future expansions.

The steps:

- Evaluate loading areas and deyelop a specific plan for resolution of connicts at each location.

- Develop truck routing plan to reduce disruption to residential streets.

- Ensure that sidewalk curb radii and sidewalk design at corners can accommodate tractor-lrai ler turning where necessary.

- Acquire land and build a central truck staging area

- Relocate wooden telephone/power poles where they obstruct movement of tractor trailers on intended access routes.

- Create several secure central employee parking lots.

- Create seyeral additional side stneet parking lanes.

3. The Look of Success: The Physical Environment

Unkempt areas lacking adequate tighting with dirty, vacant lots and bleak views from the sidewalks are associated with high crime areas. Employees and visitors worry about their cars and are willing to walk only short distances. Down·at-the-beels appearance produces fear that has an unmeasurable but certain negative effect on business, if only because it limits the labor pool.

The steps:

- Develop a simple, paint-based identity kit, establishing color standards for walls (including graffiti patch over) and a transition detail at 10′ paint line.

- Select an alternative to galvanized chain link as district-wide standard.

- Develop a matching fund incentive program so that when PRIDE businesses replace present fencing, they pay no more for district standard fencing and gates.

- Select standard specifications for sidewalks to guide replacement projects.

- Select sta ndards for district “street furnishings” such as trash cans and pedestrian lighting along sidewalks.

- Develop a district wide planting plan to include street trees where appropriate, in-sidewalk planting strip at the edge of parking lots, and ornamental planting at building entrances.

- Improve vacant and underutilized lots.

4. PRIDE After Dark: The Nighttime Environment

Dumping, vandalism, prostitution, break·ins and car thefts are frequent occurrences in and around the PRIDE area. Nighttime security patrols, initiated in April 1999, bave reduced criminal activity. The district will now transform the nighttime environment into a place where workers and nearby residents can feel secure. This means: increasing ligbting levels; tighting some building facades; illuminating business identity and other signage; and, locating special lighting at trouble spots.

Specific recommendations include:

- Install pedestrian-scale lighting. Mount lights on existing poles on larger easUwest streets. Mount lights on building walls of smaller north/south streets.

- Illuminate tbe surface of buildings at certain key locations.

- Illuminate business identification signage.

- Illuminate visitor/employee entrances and loading areas.

- Illuminate railroad bridges.

- Light the sidewalks on the underside of the rail bridges.

- Select lighting fixtures for each lighting task to become the design standard througbout the PRIDE area. Ligbting ror public streets and sidewalks should match fixture types already stocked and maintained by the city Street Department. Fixtures to illuminate signs and individual properties should be standardized to create a consistent appearance throughout the district and to facilitate discounted vendor pricing.

With relatively small contributions from the business owners, PRIDE has managed to launch its safe and clean program and meet some other needs principally with financial support from U,e city. Although it is not clear that the new administration in City Hall will continue this generosity, there are not yet plans for a business improvement district to produce a greater degree of self sufficiency.

Case 2: Richmond Corridor Association

The Richmond Corridor Associat ion occupies almost two square miles in an area of Philadelphia that has been an important rail and shipping center for well over a century. Bisected by Interstate 95, the principal nortb-south highway along the East Coast, there is a modern, aeLive port facility on the Delaware River side and active rail spurs connecting to the principal north south railroads, as well. The south and west sides of the district border the same working class neigbborhood as the PRIDE area.

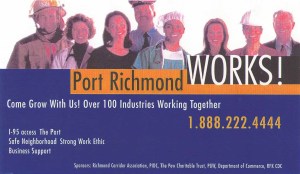

Nick Nehez, CEO of Gryphin Co., paint manufacturers, convened several of his neighbors in 1999 to consider how to improve their area. The group has grown, has received support from the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corp., and the Pew Cbaritable Trusts, and is working with a consulting team to produce a master plan for the area. In addition to the transportation advantages, the group sees the area’s assets to be the safe neighborhood; good, nearby work force; fast permitting and low costs of plant construction or expansion.

The RCA firms responded well (42 percent) to a Business Retention Survey in January 2000. Fifteen firms bad fewer than 25 employees and the two largest had 125 and 186. Sixty-six percent of employees are Philadelphia residents. Asked to rate the area in terms of its value to their businesses, about a quarter rated the area low, while more than 40 percent rated the area favorably.

Firms were asked to indicate the prospects for their remaining in the area and for expanding. A large share expect to remain: 65 percent say there is a greater than 75 percent chance they will be there in five years.1’wenty-three percent said there is a better than 75 percent chance that their business will expand.

Asked of tbose who may move what factors would influence their decision, only six of 15 mentioned taxes (in a city where high taxes are thought to explain every urban ill). Three mentioned crime or had police complaints. The balance included appearance of the area. Most respondents didn’t mention either crime or taxes.

Of those who do not contemplate leaving, the most commonly cited reason was the perceived need to stay close to the existing labor pool. One responded: “Could not get a better deal anywhere,”although another sa id “too old to move.”

Asked of those who located in the RCA area in the past ten years why they picked this place, answers included “convenient,” “material supplier nearby” and “it was a very good deal.”

The plan for the RCA area includes a business attraction, retention and expansion elemenl that responds to the RCA board’s principal concern, loss of neighboring manufaeLuring businesses. Part of the program will require an active communication element to reassure potential locators that the area is safe and the work force good. Being considered is a large sign facing I-95 featuring the successful business operators at this location with brief but prominent mention of the area’s assets. The primary message is that this ad is not simply something paid for by the city, which might be expected to say that all areas are good. It will reflect what is probably the area’s principal asset- the businesses that have come together to improve and to market the place. Who is a better testifier to a place’s economic benefit than those who run their businesses there?

An important element in tbe RCA program involves steps to capture new businesses and business related activities (such as parking) on under-developed land including city controlled acreage and land under the elevated interstate highway. Replanning streets, reparceli za tion of land and use of property controlled by the gas utility are among the objectives. RCA will bave a data base comprised of its land inventory and a roster of businesses, now totaling almost 100.

Mark Keener, the design consultant who heads the RCA advisory team, speaks of “growing an industrial strength community” in which there is mutual support among businesses and between the industrial and the residential community. His vision is to create through wayfinding and identity signs, landscaping and enhanced buildings a sense “this is a place that will endure” and in the process attract more strong firms.

Keener is also working on the small scale impediments in truck movements throughout the district, identifying where curbs and other barriers need to be modified. In addition, he is seeking new truck routes that will capture the advantages of a new I-95 on·offramp, while remaining sensitized to the need to protect schools, churches and residents.

Case 3: Camptown Industrial Park, Irvington. NJ

Irvington, NJ, is a fiscally fragile working class community whose industrial area adjoins one of Newark, NJ’s most impove risbed neighborhoods. Irvington rnanaged to get itself designated an Urban Enterprise Zone under New Jersey’s innovative and generous state law. The UEZ identified the industrial area as a priority target for organization and special benefits.

A lively group of manufacturing business owners was identified who found that they shared a desire to improve many aspects of the place where they were operating their firms. Despite the generally shabby and sometimes threatening appearance of the area, easy access to Interslate 78 and proximity to New York City has made the location a favorable setting. Sti ll , owners complain that prospective employees don’t show up for job interviews when they see where they would be working. Some firms have cut work shifls and others feel they have to hold meetings with customers at remote sites.

In the first phase, the industrial business leaders agreed to pursue four goals and 17 implementation steps (Table 3). At this writing, the group is in the process of forming a business improvement district that will enable them to use its own funds for such actions as:

- Contracting for area mobile security nights, weekends and holidays;

- Contracting for area cleaning including vacant lots, sidewalks and alleys;

- Creation and installation of directional and gateway signs; and

- Contribution to an Enterprise Zone-administered marketing fund.

As the group becomes a self-administering non-profit corporation under stale law, it will also plan and advocate for additional assistance such as pursuit of state funds for demolition of obsolete buildings and environmental clean-up.

Case 4: “An Industrial Park” in the City, Detroit, MI

ICLL stands for the streets that comprise Detroit’s first ICA – Intervale, Cloverdale, Lyndon and Livernois in West Detroit. The brainchild of manufacturer Sid Taylor, CEO of SBF Automotive, the organization’s fu ll Dame speaks of the members’ aspirations: The [CLL Industrial Park Association. Taylor and his peers asserted what leaders in the other four districts have in mind, the transformation of their LOO·acre setting from a deteriorating, disparate rollection of older production buildings into a modern “park,” the equal of any in the suburbs.

Formed in 1997, the [CLL board (called “team members”) includes four members representing manufacturing firms; a sergeant from the Tenth Police Precinct; two bank representatives; four economic development agencies; Wayne State University; Wayne County aDd a resident.

ICLL’s slick, six-page newsletter reports on recent successes:

• 85 volunteers participated in the May”‘c1can sweep” day, starting with an 8:00 AM breaklast and wrapping up at 4:30. An accumulation of illegally dumped trash was removed with business and resident help.

With the Hudson Webber Foundation support, an architectural firm completed “‘an in place industrial park plan”. The document that will guide city infrastructure improvement work that includes specifications for a much needed truck turnaround site, plus landscaping and signage.

The ICA worked with the police precinct to create a trained, two rnernber police bike patrol. The objective is to “have police officers out in the community to interact with residents and businesses as part of community policing,” the newsletter asserts.

Illegal dumping has been drastically reduced and convictions of guilty dumpers has risen.

Taylor has been effective in securing city assistance for infrastructure improvements, underscored by the photo of and statement by Mayor Dennis Aracher in the organization’s attractive newsletter. lCLL is actively considering formation of a business improvement district to assure the predictable availability of funds to accelerate creation of the industrial park.

Case 5: Paterson, NJ

The Bunker Hill Special Improvement District in Paterson, New Jersey, is an island of industrial self help io a community created by Alexander Hamilton to be the young nation’s manufacturing center. Once the “Silk City,” Paterson later was a major center for the construction of aircraft engines needed for World War II. Paterson retains some of its manufacturing, much of it in the mile square Bunker Hill area where 120 businesses formed a business improvement district five years ago to deal with common problems.

Under New Jersey law, non profit corporations can prepare plans for common services and improvements which, when approved by the City Council, permit an assessment on benefitting properties to finance approved costs. Under the leadership of former CEO John Fressie of the Bascom Corp., tbis procedure was followed, making Bunker Hill one of the oldest industrial improvement districts among the 1000 or so commercial BIDs in the country.

With five years experience under their belt,the corporation’s board has recorded the following achievements:

- With a nighttime and weekend security force and vastly improved cooperation with police, break-ins and other formerly prevalent crimes have been substantially reduced to the point where occasional drag racing is now listed as a remaining security issue. The mobile service costs $89,000 annually and provides coverage 108 hours a week by an experienced service provider.

- An effective contrad cleaning program picks up litter daily as well as removing occasional illegal dumping. This costs $33,000 per year. A small but growing landscaping program has put handsome Bunker Hill signs and attractive plantings at the major entryways, with more planned. Landscaping along railroad tracks is next. In addition, Passruc County financed a tree planting project and the district has installed bannelS to reinforce its identity.

- Working with the local utility, lighting has been made brighter in several previously dim locations. With some firms operating two and three shills, this added reassurance has been important.

- After years of depending on volunteers, the board last year hired a part-time manager.

- The district successfully applied for funding from the city’s Urban Enterprise Zone to reconstruct one badly deteriorated street. The board is currently exploring the possibilities of a daycare program.

The $168,000 budget and assessment level has not been raised since the district was formed. Manager Tom Lonergan says the district’s problems are now relatively few as crime has been reduced. the area is well maintained and the overall appearance made fit for successful businesses. More ligbting would be a help, he says, and the board would like to end dumping. “It’s working; says Lonergan who splits his time between the Bunker Hill district and the city’s downtown commercial BID.

Some of the difference in accomplishments suggested in Table 4 is the result of Richmond Corridor and Irvington having been around less time than the other three. Bunker Hill began by planning a business improvement district, assuming that unless the cooperating businesses were able to raise funds themselves, they would make little progress. As it is, the non-profit corporation has thus far raised more than a million dollars, principally for security, cleaning and beautification.

There are still only a few BIDs serving manufacturing and distribution complexes (Table 5). Some state laws authorizing districts are so slanted at commercial areas that industrial BIDs are at best in cloudy legal territory. New Jersey’s law is among the most user friendly, offering great flexibility in terms of assessments, governance, authorized services and improvements.

Elements of Success

ICAs are setting ambitious cou rses for themselves, with 20 projecl and organizational activities already achieved or on their lists of intended activities. Bunker Hill in Paterson, NJ, with more than five years of working experience behind it, has the greatest number of accomplishments. It has, moreover, its own financing through the business improvement district wbich has produced more than $800,000 during that period, mainly devoted to contract safe and clean services. Further, the new part time staff person should produce more financial support for capital improvements.

What are the factors that contribute to the successful organization and operation of ICAs? In the five cited cases, these seemed to be the common elements:

- Shared Concerns -There must be a sense of common needs. These can range from positive visions of opportunities w accumulated anger about rampant graffiti or grievances regarding actions or inactions of the city government.

- Cooperation Potential – There must be some recognition of opportunities, such as area security, that can only be realized by cooperation among all participants.

- Common Turf – Closely related w these is a sense that the individual businesses occupy terriwry that is demonstrably common. While many old city residential neighborhoods have names and a strong sense of place, this is not always true for industrial areas. Defining the fledgling organization’s jurisdiction is an early and important step in organization.

- Leadership -There must be at least one business owner who is wi lling to get the ball rolling. This was John Frennie in Paterson. In the PRIDE area, Alan Woodruff (Haskell-Dawes, Inc.) was among the small group that responded w the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corp’s suggestions about the possibilities of cooperative activity. There must be someone who is willing to take the added time to be a leader and lhe group must be responsive to that person as the leader.

- Want to Stay -There must be a considerable number of owners who want to keep their operations in place or who, for whatever reasons, cannot reasonably move away. A good deal ofthe energy of these groups will come from those who are new (arrived less than ten years ago) or are currently owned by relatively young persons. These owners contemplate long tenure and the opportunity to realize substantial improvements in the business environment.

Writing of a pioneering industrial initiative in Philadelphia, manufacturing expert Gregg Lichtenstein says, “There is growing sentiment that something is missing in the current model of economic development.” Lichtenstein says that many businesses don’t trust the advice of economic development serv ice providers because they perceive them as “motivated to sell the particular solutions they are offering_'” Moreover. few programs are geared to helping existing firms remain and prosper.

Governmenl-designed and managed economic development remedies are often wholly adequate to remedy capitalism’s ills. Part of what’s missing may be business-planned and initiated actions, such as these five cases reflect.

Another missing piece may be gleaned from the observation that the ICA firms typically defined their problems as place related. In meetings and in survey responses they complained of crime, dirt, poor street lighting, inadequate or poorly maintained streets, inadequate directional signage, illegal dumping, abandoned cars and vacant buildings and they decried the loss of businesses influenced by these conditions. More important, they feel so strongly about these conditions that they are engaged in their remediation. Place-related issues are not typically the concerns of economic development organizations.

Value Added?

In view of the extensive network of federal, slate, regional, county and municipal level governmental, quasi-governmental and non-governmental economic development agencies and organizations, what added value can ICAs bring to the table? While this will vary renecting the priorities of their private sector boards of directors, these four benefits appear to be generic and worthy of consideration because of how they differ from traditional public remedies.

- No amount of jaw-boning by economic development professionals from distant offices can prove as persuasive to a site-seeking business prospect as the straight-from-the-horse’s-moulh testimony by one or more manufacturers happy with the location his or her firm has occupied for ten or 20 years. The existence, moreover, of an organization of like-minded business people who devote time and money to collaborative improvement of business prospects adds convincing weight to the assertion that this place is a good risk. If an area doesn’t pass this test, the grants, loans and tax incentives won’t be needed.

- The improvements guided by an ICA over the years to make the area function better and to improve its curb appeal will reflect business judgements tempered by recognition that lhe benefits must be worth the contributions made by the same business people The underlying assumption of ICAs is that the business rewards will exceed the business costs. The practical results of these investments may be expected w prove more relevant and useful than many of the economic development improvements created using other people’s money- local, state or federal.

- Industry expert Gregg Lichtenstein is a proponent of the synergy resulting from bringing together what he regards as typically isolated industrial entrepreneurs. The opportunities resulting from regular leA-style association include: shared expenses, pooling resources, buying and selling from one another and sharing information and ideas. These reflect an important dimension of capitalism in dense, urban settings, agreeably lost in the isolation of suburban locations. Cities offer the opportunity to create new or improved methods, products and services through the stimulation of one good mind interacting with another in regular association. ICAs can be useful to the extent they foster such fertilization.

- ICAs represent group commitment to improving the product-the place-in which these firms operate. Much of economic development today represents simply marketing places, hoping no one will notice the deficiencies. Place improvement is a more important and lasting contribution to local economic advancement and is probably the most important role ICAs play.